Dr. Areef Suleman is Director of Economic Research and Statistics at the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) Institute. The views expressed in this essay are those of the author and do not imply or reflect the views of the IsDB Institute or IsDB Group.

Cross-country access and mobility are increasingly being viewed as an insurance policy against economic and political uncertainties amid the world’s precarious landscape. The Covid-19 pandemic revealed that while a global shock may strike countries similarly, the impacts still vary because of country-specific differences. In this context, investors seek to ensure a steady stream of profits and stable consumption in unpredictable times. Economic mobility in terms of visa-free access to more stable economies is one way to achieve this objective.

In this analysis, mobility is characterized both by destination and by access to economic output. Mobility in destination describes the number of destinations a passport can access visa-free. This relationship is measured using the Henley Passport Index (HPI). According to the HPI, if a passport facilitates foreign travel without the need of a visa, or through a visa on arrival, a visitor’s permit, or an electronic travel authority without requiring pre-departure government approval, then that passport is considered mobile in that destination.

An Indonesian passport can access close to a third of the world’s 227 destinations visa-free (with an HPI score of 71), which is not bad. However, if the objective is to maximize profits and stabilize economic activities, assessing the number of countries one can freely access is not a sufficient measure of mobility.

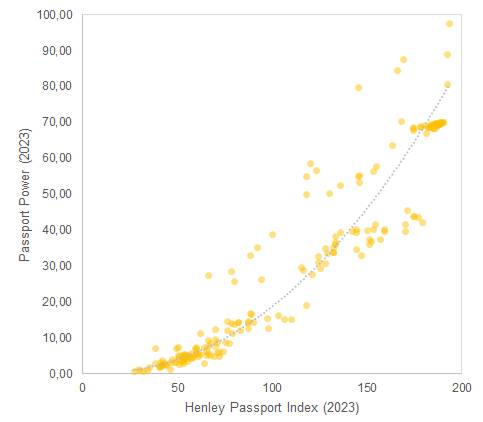

Figure 1: The Relationship between the Henley Passport Index and Henley Passport Power 2023

A better measure of mobility lies in access to economic output. Mobility in access describes the share of economic output accessible to a passport relative to the world output. This interplay is measurable using the Henley Passport Power (HPP) tool. HPP computes the gross domestic product (GDP) shares of the world’s countries, which a passport can ‘access’ visa-free (including its home country).

The 71 destinations that an Indonesian passport can access account for only about 8% of the world’s GDP (9% if including Indonesia’s own GDP), which completely changes the picture.

While some divergence exists between the HPI and the HPP scores, there appears to be a positive exponential relationship between the two (see Figure 1). This graph implies that higher HPP scores are associated with greater HPI scores, possibly because when access to larger and more stable economies is acquired, then access to many smaller economies becomes easier.

Investment migration (otherwise known as residence and citizenship by investment) is attractive to individuals who intend to maximize and stabilize their profits by diversifying their activities across more reliable economies. As such, this kind of investment is a form of insurance against the unpredictable global economic landscape. Generally, what investment migrants hope to achieve are not only the benefits within the country (social security, economic stability, or tax savings) but also the rights they secure in third countries. For example, one may migrate to St. Kitts and Nevis — a country with a GDP share of 0.001%, an HPI score of 157 destinations, and a HPP score of 38% access — because of the rights they gain within the country as well as in the rest of the 157 destinations they can travel to visa-free, including Hong Kong, Singapore, the UK, and all the countries in Europe’s Schengen Area.

Understanding the difference between mobility using HPI and HPP scores allows investors to better assess whether acquiring residence or citizenship status in another country serves their unique objectives. HPP might be a more relevant statistic in business migration because access to bigger markets is necessary for scale economies. Bigger markets are likewise associated with a larger cross-country workforce, a more stable infrastructure for business development, stronger property rights, and greater investor protection, which are all attractive market characteristics.

Greater access to the world’s economic output is desirable because it expands the basket of products available to most individuals. While increased access is also attainable through international trade, the options available with physical access are far greater, extending to the use of services that are non-exportable such as better-quality education and healthcare.

The benefits of access and diversification must be assessed against the costs — a significant portion of which is the minimum investment in residence and citizenship by investment programs.

For countries with a high HPP score (greater than 50%) and an active residence or citizenship program, an average investment of USD 631,050 will provide mobility in an average of 180 destinations or access to an average of 68% of the world’s GDP. Meanwhile, in countries with low HPP scores (less than or equal to 50%) and an active residence or citizenship by investment program, an average investment of USD 201,665 will provide mobility in an average of 144 destinations or access to an average of 31% of the world’s GDP.

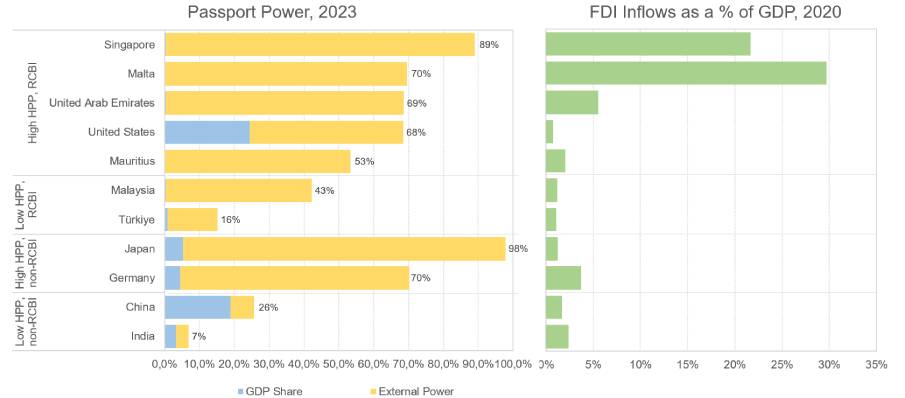

Japan and Singapore are the two countries with the highest HPP scores, at 98% and 89%, respectively. In contrast to Japan, Singapore has a residence by investment program, with a minimum investment of SGD 2.5 million (approximately USD 1.8 million). Interestingly, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows as a share of GDP are significantly larger in Singapore than in Japan (see Figure 2).

In addition, Malta, Singapore, and the UAE are investment migration host countries with small economies in terms of GDP, but they possess high HPP scores owing to strong external power. Notwithstanding their economic size, FDI inflows constitute a significant portion of their respective economies. Visibly, residence and citizenship by investment countries with high HPP scores (such as Mauritius, the USA, and the aforementioned) have greater relative FDI inflows than investment migration countries with low HPP scores (including Malaysia and Türkiye).

The two largest economies in the world, the USA and China, have HPP scores of 68% and 26%, respectively. Between these two countries, only USA has an investment migration program. However, the FDI inflows as a share of GDP is lower in the USA than in China (1% versus 2%). This discrepancy indicates that attracting FDI is affected by a myriad of economic and political factors, not just the existence of a residence or citizenship programs.

Figure 2: Henley Passport Power and Foreign Direct Investment Inflows of Selected Economies

Global development has been stalled by the Covid-19 pandemic. The post-pandemic world is characterized by tighter financial conditions and higher debt vulnerabilities. Thus, many countries aspire to financial recovery using non-debt sources.

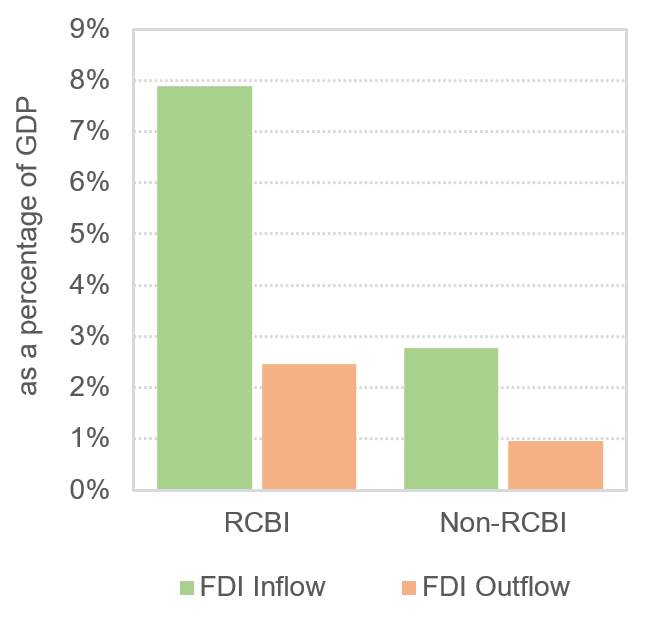

Figure 3: FDI Flows in RCBI and Non-RCBI Countries, 2020

Countries that host residence or citizenship by investment programs can take advantage of these programs to attract investments for post-crisis development. Data in 2020 indicate that investment migration countries on average attract greater FDI flows than non-residence-or-citizenship-by-investment countries (see Figure 3).

Improving a given country’s passport power seems to be a viable policy direction to strengthen the potential of investment migration programs in attracting investment. However, as cross-country access is not determined unilaterally and is cemented by longstanding treaty agreements, countries must not only focus on improving diplomatic relationships but also on enhancing domestic institutional stability.

Notes